|

|

|

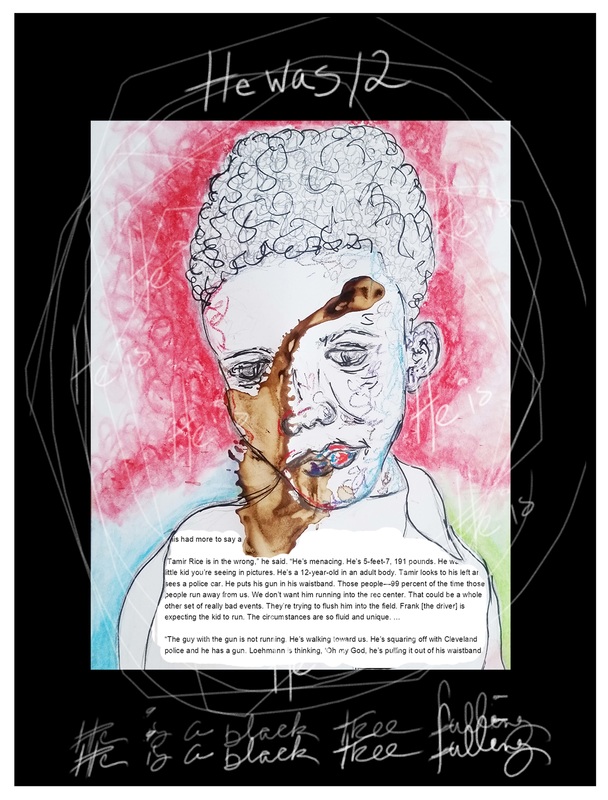

So the purpose of this project is to do just that— take control of a narrative that, by fact and by law, has silenced black voices and black bodies through an erroneous rewriting of our stories and an in-authenticating of our existence. In order to do this, Controlling the Narrative seeks to recover and retell the stories of a multi-generational group of ancestors and descendants through community conversations, video, and a 3-act play all based on the similar themes that emerge out of the narratives of past and present youth and adults of color. These goals will be accomplished through completion of the following: 1. engage in the facilitation of authentic African American identity through recovery, preservation, and presentation of primary documents, oral testimonies, individual, family and community stories, and images of African American ancestors and their descendants as well as documentation, preservation, and presentation of community stories of young African Americans currently living in the Edison, Northside and East Side neighborhoods in Kalamazoo that would have been peers of Tamir Rice, Aiyana Stanley-Jones, Michael Brown or Renisha McBride had they survived, in hopes these stories prove that the “those peopling” that so many Steve Loomis’ seem to write, wrong 2. re-pen, repaint and thus restore authentic black identity to the individual, to the black community and to larger culture through production of the following: a. a 3-act play that reflects the authentic narratives, and b. facilitate multiple, creative and layered community conversations that use the authentic narratives and documents, the ancestors, the descendants, the young people and the larger community to talk to each other in order to begin to accurately rewrite us. And this controlling the narrative is essential to our survival since shooting a black boy or girl or unarmed adult is so much more difficult to do, to justify or to acquit than shooting a savage, an animal or a criminal. We must have our own names in our own mouths. We must control the narrative because to control the narrative is the means to controlling our individual and collective survival.